The graphic shows the latest IMF projections for world growth. Those interested can find full details here.

There is a dreadful fascination in watching the global financial crisis unwind. I wish I had a spare billion or two to invest at a personal level just at present. There are some interesting investment opportunities emerging.

I must say that I find some of the continuing discussion confusing because it mixes together so many very different issues. It is quite hard to stand back and look to the longer term.

This post is intended to clarify my own thinking.

Financial vs Real Economy

In Why the US financial package should be rejected - and why Australia will ride out the storm I suggested that one problem with the US Rescue Package lay in the way it mixed together two very different things. The first was the maintenance of liquidity, I should add here the restoration of confidence, so that financial institutions could lend to each other. This was a good thing. The second appeared to be the maintenance of US property values. I thought that this was plain silly.

Economists usually make a distinction between the financial and real economies. One of our problems just at present is that the two have got out of kilter along three dimensions.

Dimension one is a shift in the relative size of the two. The sheer volume of transactions dwarfs the physical economy. One consequence has been greater instability in key markets on which the physical economy depends. The current financial crisis is but one, if the largest, in a long series. The traders have acquired a life of their own.

Dimension two is the way in which the financial markets have supported, leveraged, the growth in value of certain types of assets. During the long boom period, this supported rises in corporate and consumer debt, in turn fuelling demand. However, the process also resulted in a growing gap between the real sustainable value of assets and market prices .

.

Dimension three is the growth in the size of the financial sector itself within the real economy.

If you look at the attached chart from the New York Times, you can see that over the last thirty two years, the finance sector's share of total US wages and salaries rose from just over 5 per cent to 9.8 per cent. During that same period, its share of US corporate profits rose from around 17 per cent to 27.4 per cent.

What goes up is likely to come down. The problem we now have is that all three dimensions have gone into reverse at the same time. Leveraged growth has turned into leveraged decline.

I am not saying anything new in any of this. However, I am not sure that people fully realise the implications.

In past busts of this type, one outcome has been a relative decline in asset prices until a new value equilibrium is reached. This creates pain, but also lays the basis for subsequent growth. The scale of the problem this time, the way in which de-leveraging has been wiping out corporate and individual value in certain countries, creates a desire to try to maintain asset prices.

The problem here is that success is likely simply to prolong problems. We may stop collapse, but many countries may face stagnation until real equilibrium in asset values is restored.

Australia remains the lucky country in all this. We have a long history of booms and busts. We were not immune to the global financial boom. However, this time a number of things have combined to work in our favour. Here three things are of particular importance.

The first has been our improved terms of trade as a consequence of rising food and commodity prices.

Australian commentators have talked about the emergence of a dual economy, a flat economic sector especially in NSW on one side, booming resource economies on the other. What is, I think, less clear, is that this has cushioned an adjustment process that began some time ago.

As an example, Australian residential construction is close to record lows because of the end of the previous housing boom, but the economic effect has been contained. Our worry now is how to expand housing, not to preserve asset values but to meet a rental shortage.

The second thing working in our favour is that our excesses were simply less. As a consequence, we do not have the type of systemic problems that exist in some other countries. Among other things, this means that Australians are (so far at least) simply not worried about domestic bank crashes. It just won't happen.

This links to the third thing working in our favour, the way our official systems have worked.

Worried about excessive demand and potential inflation, our Reserve Bank has been tightening monetary policy for some time. Over the last few years, we have seen interest rates rise steadily as the Bank sought to contain the economy. With high interest rates by world standards, there is now scope to cut.

At fiscal level, the booming economy has allowed for budget surpluses and debt repayment. At national level, we have no net official debt. I have argued that this process has gone too far, but no-one can argue that it has not put us in a strong position to use fiscal policy to support expansion if we need too.

One interesting side-effect that I had not focused on is that Australia now has the sixth largest Sovereign Wealth Funds in the world. I have not written about this before, but should do so. Australia also has a large and growing pool of investible funds because of the impact of the superannuation guarantee levy.

All this means that we are in an unusually good position to ride through current troubles.

Shifts in the economic tectonic plates

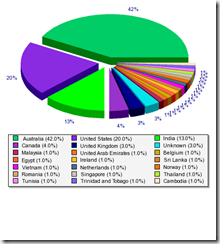

If you look at the IMF projections, you can see that the IMF believes that while developed economies will enter recession, growth will continue in some of the developed economies including India and China.

As I see it, the current global financial crisis is like an earthquake marking a shift in the economic tectonic plates. As part of this, the share of the global economy held by the big emerging economies will increase.

Of course they will be affected by the downturn. We can see this in China already with downturns in certain sectors linked to export markets. I actually think that the impact will be greater than the IMF allows. However, it remains true (as the IMF suggests) that these economies have significant capacity to expand domestic activity to compensate.

From the viewpoint of China, the current downturn may be a blessing in disguise. China has been suffering from rising input costs. These were going to squeeze some export activities anyway. The global downturn provides China with the opportunity to expand domestic investment and consumption at a lower price than might otherwise be the case.

Australia may suffer in the short term because of lower commodity prices, but we can still make a fair bit of money.

Conclusion

I suppose my key point in all this at global level is that we need to keep a sense of perspective on the changes. At local level, I feel that Australia remains the lucky country.