In my last post, A non-economist's crib to Australia's economic outlook - part one, I focused on the views of Reserve Bank Deputy Governor, Ric Battellino on the current reasonably strong financial position of the Australian household sector.

In this post, I want to look at the latest Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook prepared by the Commonwealth Treasury. There has been much commentary on this in yesterday and today's media, looking especially at some of the headline numbers. My concern is what we might learn from the document about Australia's economic outlook. All numbers are in $A unless otherwise noted.

The Official Position

At the time of the May budget, the 2008-2009 Australian Government cash budget surplus (accrual figures are a little higher) was projected at $21.7 billion. This has now shrunk to $5.4 billion. A pretty big fall.

If we look at the reasons for the fall, we find that projected expenditure has risen by $10.6 billion, largely due to the recently announced fiscal stimulation measures.

Taxation revenue is projected to fall by $4.9 billion, largely because of falls in receipts from capital gains and company tax.

Turning now to the forward estimates. For the benefit of international readers, these are longer term budget projections taking into account approved expenditure, including the Rudd Government's election commitments.

The forward estimates show projected cash surpluses of $3.6 billion in 09-10, $2.6 billion in 10-11, rising to $6.7 billion in 11-12.

The headline $40 billion figure used by many commentators to describe the total deterioration in the Australian Governments financial position is the combined change in the surplus from budget time for the total period from 08-09 to 11-12. Expressed in this way, the change is not quite as dramatic as might appear at first sight.

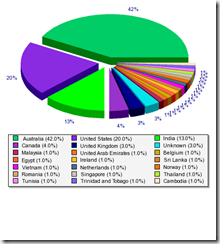

In considering the projected surpluses, I was struck by the following chart (2.2), showing the projected budget position in various developed countries. Australia and Canada stand out. I will discuss some of the economic assumptions on which the projections depend in a little while. For the moment, Is imply note that the figures are indicative of Australia's comparatively strong position.

Chart 2.2: Budgetary positions for selected countries in 2008 and 2009  For the benefit of international readers, I should add that Australia's budget figures, while subject to a range of assumptions so that outcomes are generally a little different, are not rubbery. The Australian Treasury values its reputation.

For the benefit of international readers, I should add that Australia's budget figures, while subject to a range of assumptions so that outcomes are generally a little different, are not rubbery. The Australian Treasury values its reputation.

A further point to note is that Australia's position is very different this time as compared to the previous big crashes of the 1890s and the Great Depression. In both cases Australia was heavily dependent on international borrowings. In this case, the Australian Government has no net debt, adding to fiscal flexibility.

It is important to be clear here.

One measure of international indebtedness shows Australia with high and growing debt. However, that debt is private. The Australian Government's net debt position is positive to the tune of around $47 billion, with debt more than offset by things like the Future Fund, Australia's largest sovereign fund. The Government actually gets more interest than it pays! Full marks to Mr Costello as former Treasurer.

All this leads, as shown in the chart below, to immediate growth projections far better than those in most developed countries.

Chart 1.1: Forecast economic growth rates for G7, Euro area and Australia in

2008 and 2009

But are these better growth projections over-optimistic? To make a judgement here, we need to look at the economic assumptions. Australians will have noted just how careful the current Treasurer is in his comments. It's not easy making assessments in an economic firestorm.

But are these better growth projections over-optimistic? To make a judgement here, we need to look at the economic assumptions. Australians will have noted just how careful the current Treasurer is in his comments. It's not easy making assessments in an economic firestorm.

The Assumptions

I am not going to be too detailed in the following comments. After all, this is a crib, not a full scale analysis. Further, the variables are all inter-related, so a change to one flows elsewhere through the system. Treasury uses full scale economic models to test this. I will just point to the linkages.

We all know that Australia has been through something of a resources boom and that our terms of trade (the price we receive for our exports compared to the price of imports) had improved. I was struck by the chart (3.3) showing movements in the terms of trade since 1940.

Australia has been through something of a resources boom and that our terms of trade (the price we receive for our exports compared to the price of imports) had improved. I was struck by the chart (3.3) showing movements in the terms of trade since 1940.

The huge spike in 1950-1951 is the wool boom where demand for uniforms for the Korean War on top of rising consumer demand sent the prices we received for our wool through the ceiling. Wool reached a pound a pound, to the joy of our rural community.

With spikes, our terms of trade then declined until the early nineties. This meant that we had to sell more to get the same volume of imports. Then we had the huge resources boom. We sold more and at increasing prices, while the prices of our imports stayed down because of the emergence of new suppliers and especially Chin a. We were indeed the lucky country.

a. We were indeed the lucky country.

This period has now come to an end. Chart 3.2 shows the collapse in the spot price for two key commodity exports, iron ore and coal. Now here we need to take into account price and volume effects.

We have existing contracts that will hold at least some prices up in the short term. Then prices for commodities can be expected to fall towards the spot price, so that our terms of trade will deteriorate.

To accommodate this, the Treasury projections forecast a decline in the terms of trade of 8½ per cent in 2009‑10. As a result, nominal GDP growth in 2009‑10 is forecast to grow by only 3 per cent, compared to growth of around 8 per cent over the last two years.

Export prices are usually expressed in US dollar terms, while producers receive Australian dollars. This means that with a lower dollar, domestic receipts may stay the same so long as volume of sales hold up, a cushioning effect. In this context, the projections assume that the Australian dollar will stay at a lower level, with reduced but continuing growths in volume because of lower but continued growth in certain countries and especially China.

If the terms of trade deteriorate by more than expected, if the Australian dollar increases in value by more than expected, if export volumes fall, then the projections will change. The Mid-Year paper models two effects, showing how GDP growth might drop to zero or even negative.

Turning now to investment.

High business investment has been one of the recent drivers in economic growth. The projections assume that this will continue in the short term because of projects already underway, but then flatten in 09-10.

Housing investment, another past driver, has been low and falling.This is where Mr Battelino's analysis, A non-economist's crib to Australia's economic outlook - part one, comes in. He suggests, and I think that he is right, that Australia is several years in front of the US housing cycle. We do not have surplus housing stocks, really the opposite. So the projections assume a pick-up in housing in 09-10, driven in part by the first home buyer grants in the economic stimulus package.

On the Government side, the projections show the Government sector making a positive general contribution to growth, driven in part by new infrastructure spending into the medium term.

By size, consumption demand is a key part of the economy. The projections assume that growth in consumption demand will be well down in 08-09, with the economic stimulus package making a contribution in the second part of the year.

Private consumption depends in part upon expectations, more upon consumer incomes. This is where employment conditions are critical. Here the projections suggest an increase in employment of one and a quarter per cent in 08-09, well down from the original budget estimates, just 3/4 of a per cent in 09-10, rising to one and a quarter per cent in 10-11 and 11-12.

This means some rise in unemployment in the short tem at least. The unemployment rate is forecast to rise to 5 per cent by the June quarter 2009 and 5¾ per cent by the June quarter 2010.

Again, we can see the way things inter-connect. If, as seems to be happening at the moment, consumers cut back on spending because of fears for the future, then this will feed through to lower demand and higher unemployment. In this context, the present job market has become very soft.

Conclusion

Troubled times. There are obviously great uncertainties built into the projections, and indeed some commentators have already suggested that the underlying assumptions are too positive.

They may be right. However, we can say two things.

First, the projections do provide an framework for looking and assessing future economic performance independent of immediate day-to-day fluctuations.

Secondly, they and Mr Battelino's analysis do suggest why Australia is in fact in a better position to ride through the current economic storms than many other countries.

Postscript

Even as I was writing this post, the IMF was releasing new forecasts showing a further sharp fall in projected world economic growth. You can find full details on the IMF site. While the Australian economy is still projected to grow if lower than the Treasury estimates, developed countries as a whole are projected to drop into negative growth.

The new IMF forecasts illustrate the difficulty of making economic projections at a time like this, but do not invalidate the analysis in this post.

The projections have been made on the basis of current policies and ignore the effects of further stimulatory action in various countries. I must admit to a growing concern that the combined effect of the various stimulatory measures may lead to over-shoot in the opposite direction, fueling inflation in due course, leading to another round of corrective measures.

For the benefit of international readers, I should add that Australia's budget figures, while subject to a range of assumptions so that outcomes are generally a little different, are not rubbery. The Australian Treasury values its reputation.

For the benefit of international readers, I should add that Australia's budget figures, while subject to a range of assumptions so that outcomes are generally a little different, are not rubbery. The Australian Treasury values its reputation.